What's really unhealthier - binge drinking or a small daily tipple? | Daily Mail Online

The results of this unique experiment - by identical twin

doctors - will surprise you

- Chris and Alexander van Tullekens star in a BBC Horizon show

- Documentary about alcohol will study effects of 21 units of alcohol a week

- Chris drinks them spread out over the week for one month

- Alexander drinks them all in one binge session once a week for a month

- Will these different drinking patterns affect their health?

- Horizon: Is Binge Drinking Really That Bad? is on 9pm, Wednesday, BBC2

Not long ago, I used to envy people who earn a living reviewing fancy

restaurants or taking all-expenses paid holidays in exotic locations.

Imagine making money doing stuff the rest of us pay for!

But now I've had one of those dream jobs - I was essentially paid to get drunk - and it was horrific.

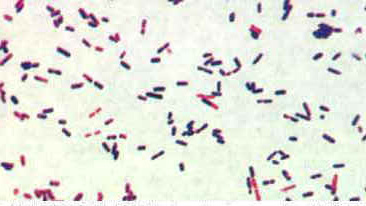

After just one month I'd caused widespread and serious damage to my entire

body, while my blood was being poisoned by bacteria that had leaked from

my gut.

And if you think this has nothing to do with your life, I'm afraid you'll have to think again.

Scroll down for video

Dr Chris van Tulleken (L) and Dr Alexander van Tulleken (R) star in a BBC Horizon programme about alcohol

My assignment had come about as part of a documentary I've made for BBC

Horizon with my identical twin brother - we're both doctors specialising

in infectious diseases. We wanted to look at binge drinking and whether

it really is as bad as we're told.

It's a very important question because it's how a lot of us like to drink.

Many of us can't afford the time or the money to drink every night. And

besides, like many people, if I'm having a drink I like to feel the

effects properly - I admit I like more than one glass.

The obvious answer to the question of how bad binge drinking really is, is

that it's terrible. I was an A&E doctor for six months and there

were nights when I saw nothing but alcohol-induced injuries: car

crashes, falls, domestic violence and more.

But apart from raising your risk of injury, how bad is binge drinking when it comes to your health?

The

UK Government defines a binge as double the maximum 'safe' daily limit

for alcohol intake. For men that means a binge is eight units, or four

pints of lower-strength beer; for women it's six units or two large

glasses of wine.

For

many of us that isn't going to land us in A&E. It also doesn't feel

like a binge at all, more like winding down at the end of a long day.

For some it might seem like a fairly quiet evening!

So

my brother Chris and I undertook an experiment, using ourselves as

guinea pigs to assess just what binge drinking does to the human body.

Among other things, we wanted to find out if a little daily alcohol is

better for you than none at all - and does a gap between binges allow

your liver to recover?

These questions are important because the current data on how alcohol causes harm or benefit is contradictory.

Of

course, there is abundant evidence that alcohol is bad for you, causing

liver disease, brain diseases, heart disease and massive social and

psychological problems.

+4

Dr Alexander van Tulleken, who binge drinks once a week for a month in the show, breathalyses himself

Currently,

the UK government recommends that you take 48 hours off after 'heavy

drinking' and the idea of a 'liver holiday' has some medical evidence to

back it up.

A

study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology in 2006

suggested that drinking on only one to four days per week (and taking a

'liver holiday' for the remaining days) is better than daily drinking

for male heavy drinkers.

But

we don't actually have very good data for any of our alcohol

guidelines. Some studies suggest teetotalers die sooner than alcohol

drinkers, while animal studies show myriad benefits from compounds found

in wine.

My first binge was 21 shots of vodka in about four hours. The results were first comical and then deeply concerning

We

wanted to try to tidy up the mess. For the experiment, Chris and I

would drink exactly the same amount each week for four weeks, but in

very different ways.

We

would stick to the low end of the government guidelines for men, which

is 21 units per week or three units per day. Chris would drink three

units every day, which counts as moderate drinking, and I would drink

exactly the same amount, but in one go on a Saturday night. (We were

completely alcohol free for four weeks beforehand, so we started in the

same condition.)

I

began the experiment feeling confident: I was the twin who was going to

have a big binge every Saturday night and I was sure I'd got the better

deal. Not least because the liver is an organ that can withstand huge

amounts of abuse, so six days seemed like loads of time to recover

between binges.

My

thinking was I'd have a hangover on Sunday and then I'd be productive

the rest of the week. Chris on the other hand would be getting in from

work, then drinking his single glass of wine or pint and-a-half.

His

liver, brain and heart would never get a break and he'd never have any

fun. I was confident that drinking my way would be no more physically

harmful and much more enjoyable. And the BBC would underwrite my drinks!

What could be better?

My first binge was 21 shots of vodka in about four hours. The results were first comical and then deeply concerning.

Drunkenness

is often said to have a number of stages: verbose, grandiose, amicose

(the 'you're my best friend' stage), bellicose, morose, lachrymose (the

weepy stage), stuperose (the incoherent stage) and comatose. Basically

going from chatty to unconscious via being fun and then weepy.

I

was a textbook example of each stage: shouting, argumentative, talking

gibberish, then trying to get the film crew to come out for dancing and

karaoke.

I

don't recall anything after the first two hours, by which time I'd had

about 16 shots, so I only know about the next two hours (before I passed

out) because Chris filmed them. I had got wildly angry about my shoe

laces and spent the final half hour crying inconsolably before slipping

into unconsciousness.

It

was utterly undignified, the hangover was horrendous and I wasn't sure I

was going to manage three more weeks of this: I never wanted to drink

again.

It

was all made much worse by having needles stuck in me. For as part of

the experiment Chris and I had a range of blood tests devised by one of

the best liver teams in the country.

Hepatologists

Dr Gautham Meta and Professor Rajiv Jelan, at the Royal Free Hospital

in London, used tests that were so advanced they had previously only

been undertaken in animal studies - they measured chemicals in our blood

called interleukins and cytokines, which are extremely sensitive

markers of inflammation and disease.

A

few days after my first binge, I had recovered and was back to my usual

self, confident that this was doing me no real harm. The next Saturday I

did my binge differently - pacing myself with a couple of pints at

lunch, afternoon cocktails, and a bottle of wine with food.

+4

The van Tullekens with 21 units of alcohol in front of them, which they drink weekly for a month

Again,

all 21 units in one day but a drinking pattern that might not seem so

different from what many people get up to over a weekend.

My

video diary at midnight was articulate and sensible - no embarrassing

singing or irrational behaviour. I couldn't have driven a car because I

was well over the limit, but I didn't seem drunk. Next day I felt fine

and the last two binges weren't just easy, they were fun.

Chris,

meanwhile, was actually faring worse. Having a compulsory three units

every day was just enough to make him want more and to disrupt his sleep

if he drank it late after a long day at work. But not enough to have

fun. He looked forward to the end of the experiment.

I was feeling confident about the results, but the findings were shocking in several ways.

My

levels of cytokines and interleukins, those key markers of

inflammation, were raised. I'd expected them to be sky high after the

first binge - but six days later, just before I was about to start the

second binge, they hadn't gone down at all, and at the end of four weeks

they'd soared.

Having a compulsory three units every day was just enough to make Chris want more and to disrupt his sleep

I

felt good but my body was still damaged from the binge. Inflammation is

linked to a vast array of diseases from cancer and severe infection to

heart disease and dementia. This was not a good result.

Perhaps

even more disturbingly Chris had almost the same results: the three

units per day were doing him significant harm, too. So from that it

seemed the amount we were drinking was more important than the way we

drank it.

Wrong!

There

was one huge difference between me and Chris. The blood tests also

revealed I had three times the amount of 'bacterial endotoxin' in my

blood - what this means is that the binge was so irritating to the

lining of my stomach and intestines that they had begun to leak bacteria

into my bloodstream.

I

was being poisoned by my own gut bacteria and it was doing me serious

harm. We don't yet know exactly how much you have to drink to cause this

effect, but it's likely to be much less than I was drinking.

I

had thought that alcohol was safe and probably beneficial in moderate

doses. But what our experiment showed was that government guidelines are

misleading in several ways.

+4

It seemed the amount they were drinking was more important than the way they drank it

First, 48 hours off after a binge isn't nearly enough. We don't know how long you need, but it is likely to be weeks not days.

Second,

there probably isn't a 'safe' lower limit for alcohol. We'll have more

answers soon as the Royal Free is running a larger study looking at what

happens when people who routinely drink within the guidelines stop

drinking for a month. Now, all this would seem to be contradicted by a

steady stream of articles about the health benefits of red wine and

other kinds of alcohol.

And

there is good evidence to suggest that if you're a man between 50 and

60, and at some risk of heart disease, the positive effects of alcohol

on your heart will outweigh the increased risk of cancer and liver

disease.

But

- and this is a depressing but - we're talking about one small glass

per day. More than that and the harm seem to outweigh the benefits.

As

part of our research, Chris and I also looked at the way each person

responds to alcohol - by taking a group of British people with different

ethnic origins - Irish, Chinese and Taiwanese - out for drinks. The

differences were extraordinary.

There

are several genes that control how we break down alcohol and those

genes are strongly associated with ethnicity. They affect our risk of

cancer, liver disease and hangovers.

3 1/2

The number of teaspoons of sugar in a 250ml can of gin and tonic

Essentially,

the genes that process alcohol more slowly are increasingly common as

you head east from Europe, with the highest in China and Japan.

Genes

from his Irish ancestry helped our volunteer hold his drink better than

the others (although this won't be true for all those with Irish

ancestry, and to complicate the picture, our Irish volunteer was of

mixed Irish/Indian origin).

What this showed us was the idea of universal government guidelines is misleading: you have to drink right for your body type.

As

a rule of thumb: if you go red when you drink, or if your hangovers

start quickly and are severe, you're at higher risk for several

diseases. Your body is telling you to cut down for a reason. After all

this I haven't stopped drinking, but I think more about what I get out

of each drink.

The fact is, drinking is not all bad: it really does help you make friends, and it helps many of us romantically and socially.

These things are important: friends and partners help us live better and longer. But drinking is not good for our health.

All

of us - doctors, patients, publicans, public health officials,

multinational drinks companies - love the idea that alcohol might be

good for us and binge drinking might not be that bad, and want this to

be true. The sobering reality is that it isn't.