Pathogenic Clostridia, including Botulism and Tetanus (page 1)

(This chapter has 4 pages)

Clostridium botulinum

Clostridia

The genus

Clostridium consists of relatively large, Gram-positive,

rod-shaped

bacteria in the Phylum Firmicutes

(Clostridia is actually a

Class in the Phylum).

All species form endospores

and have a strictly fermentative type of

metabolism.

Most clostridia will not grow under aerobic conditions and vegetative

cells

are killed by exposure to O2, but their spores are able to

survive long

periods of exposure to air.

The clostridia are ancient organisms that live in virtually all of

the

anaerobic habitats of nature where organic compounds are present,

including

soils, aquatic sediments and the intestinal tracts of animals.

Clostridia are able to ferment a wide variety of organic compounds.

They produce end products such as butyric acid, acetic acid, butanol

and

acetone, and large amounts of gas (CO2 and H2)

during fermentation of

sugars.

A variety of foul smelling compounds are formed during the fermentation

of amino acids and fatty acids. The clostridia also produce a wide

variety

of extracellular enzymes to degrade large biological molecules (e.g.

proteins, lipids, collagen, cellulose, etc.) in the

environment

into fermentable components. Hence, the clostridia play an important

role

in nature in biodegradation and the carbon cycle. In anaerobic

clostridial

infections, these enzymes play a role in invasion and pathology.

Most of the clostridia are saprophytes, but a few are pathogenic for

humans, primarily Clostridium

perfringens, C. difficile, C. tetani and C. botulinum. Those that are pathogens

have primarily a saprophytic existence

in nature and, in a sense, are opportunistic pathogens. Clostridium

tetani and Clostridium botulinum produce the most potent

biological

toxins known to affect humans. As pathogens of tetanus and food-borne

botulism,

they owe their virulence almost entirely to their toxigenicity. Other

clostridia,

however, are highly invasive under certain circumstances.

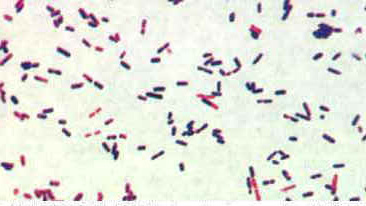

Stained pus from a mixed

anaerobic

infection. At least three different clostridia are apparent.

Clostridium perfringens

C. perfringens

Clostridium perfringens, which produces a huge array of

invasins

and exotoxins, causes wound and surgical infections that lead

to

gas

gangrene, in addition to severe uterine infections.

Clostridial

hemolysins and extracellular enzymes such as proteases, lipases,

collagenase

and hyaluronidase, contribute to the invasive process. Clostridium

perfringens

also produces an enterotoxin and is an important cause of food

poisoning.

Usually the organism is encountered in improperly sterilized (canned)

foods

in which endospores have germinated.

Food poisoning

Clostridium perfringens is classified into 5 types (A�E) on

the basis of its ability to produce one or more of the major lethal

toxins, alpha, beta, epsilon and iota (α, β, ε, and ι). Enterotoxin

(CPE)-producing (cpe+) C.

perfringens type A is reported continuously as one of the most

common food poisoning agents worldwide. An increasing number of reports

also implicate the organism in 5%�15% of antibiotic�associated

diarrhea (AAD) and sporadic diarrhea (SD) cases in humans, as well as

diarrhea cases in animals.

Most food poisoning strains studied carry cpe in their

chromosomes; isolates from AAD and SD cases bear cpe in a

plasmid. Why C. perfringens strains with cpe

located on chromosomes or plasmids cause different diseases has not

been satisfactorily explained. However, the relatively greater heat

resistance of the strains with chromosomally located cpe is a

plausible explanation for these strains' survival in cooked food, thus

causing instances of food poisonings. The presence of C.

perfringens strains with chromosomally located cpe in

1.4% of American retail food indicates that these strains have an

access to the food chain, although sources and routes of contamination

are unclear.

An explanation for the strong association between C. perfringens

strains with plasmid-located cpe and cases of AAD and SD

disease may be in vivo transfer of the cpe plasmid to C.

perfringens strains of the normal intestinal microbiota.

Thus, a small amount of ingested cpe+ C. perfringens

would act as an infectious agent and transfer the cpe plasmid

to cpe� C. perfringens strains of the normal

microbiota. Conjugative transfer of the cpe plasmid has been

demonstrated in vitro, but no data exist on horizontal gene

transfer of cpe in vivo, and whether cpe+ strains

that cause AAD and SD are resident in the gastrointestinal tract or

acquired before onset of the disease is unknown.

Case Study

Report of C. perfringens Food

Poisoning

Clostridium perfringens

is a common cause of outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United

States,

especially outbreaks in which cooked beef is the implicated source.

This

is a condensed version of an MMWR report that describes an outbreak of

C.

perfringens gastroenteritis following St. Patrick's Day meals of

corned

beef. The report typifies outbreaks of C. perfringens food

poisoning.

Report

On March 18, 1993, the

Cleveland

City Health Department received telephone calls from 15 persons who

became

ill after eating corned beef purchased from one delicatessen.

After

a local newspaper article publicized this problem, 156 persons

contacted

the health department to report onset of diarrheal illness within 48

hours

of eating food from the delicatessen on March 16 or March 17. Symptoms

included abdominal cramps (88%) and vomiting (13%); no persons were

hospitalized.

The median incubation period was 12 hours (range: 2-48 hours). Of the

156

persons reporting illness, 144 (92%) reported having eaten corned beef;

20 (13%), pickles; 12 (8%), potato salad; and 11 (7%), roast beef.

In anticipation of a large

demand

for corned beef on St. Patrick's Day (March 17), the delicatessen had

purchased

1400 pounds of raw, salt-cured product. Beginning March 12, portions of

the corned beef were boiled for 3 hours at the delicatessen, allowed to

cool at room temperature, and refrigerated. On March 16 and 17, the

portions

were removed from the refrigerator, held in a warmer at 120oF

(48.8oC), and sliced and served. Corned beef sandwiches also

were made for

catering

to several groups on March 17; these sandwiches were held at room

temperature

from 11 a.m. until they were eaten throughout the afternoon.

Cultures of two of three

samples

of leftover corned beef obtained from the delicatessen yielded greater

than or equal to 105 colonies of C. perfringens per

gram.

Following the outbreak,

public

health officials recommended to the delicatessen that meat not served

immediately

after cooking be divided into small pieces, placed in shallow pans and

chilled rapidly on ice before refrigerating, and that cooked meat be

reheated

immediately before serving to an internal temperature of greater than

or

equal to 165oF (74 C).

Analysis

C. perfringens is a

ubiquitous,

anaerobic, Gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus and a frequent

contaminant

of meat and poultry.

C. perfringens food poisoning is characterized

by onset of abdominal cramps and diarrhea 8-16 hours after eating

contaminated

meat or poultry. By sporulating, this organism can survive high

temperatures

during initial cooking; the spores germinate during cooling of the

food,

and vegetative forms of the organism multiply if the food is

subsequently

held at temperatures of 60-125oF (16-52oC). If

served without

adequate

reheating, live vegetative forms of C. perfringens may be

ingested.

The bacteria then elaborate the enterotoxin that causes the

characteristic

symptoms of diarrhea and abdominal cramping.

Laboratory confirmation of C.

perfringens foodborne outbreaks requires quantitative cultures of

implicated

food or stool from ill persons. This outbreak was confirmed by the

recovery

of greater than or equal to 105 organisms per gram of

epidemiologically

implicated food. An alternate criterion is that cultures of stool

samples

from persons affected yield greater than or equal to 106

colonies

per gram. Stool cultures were not done in this outbreak.

Serotyping

is not useful for confirming C. perfringens outbreaks and, in

general,

is not available.

Corned beef is a popular

ethnic

dish that is commonly served to celebrate St. Patrick's Day. The errors

in preparation of the corned beef in this outbreak were typical of

those

associated with previously reported foodborne outbreaks of C.

perfringens. Improper

holding temperatures are a contributing factor in most C.

perfringens

outbreaks

reported to CDC. To avoid illness caused by this

organism, food should be eaten while still hot or reheated to an

internal

temperature of greater than or equal to 165oF (74oC)

before serving.

Gas gangrene

Gas gangrene generally occurs at the site of

trauma or a recent surgical wound. The onset of gas gangrene is sudden

and dramatic. About a third of cases occur on their own. Patients who

develop this disease in this manner often have underlying blood vessel

disease (atherosclerosis or hardening of the arteries), diabetes, or

colon cancer.

Clostridium perfringens

produces many

different toxins, four of

which

(alpha, beta, epsilon, iota) can cause potentially deadly syndromes.

The toxins cause damage to tissues, blood cells, and blood vessels.

Gas gangrene is marked by a high fever, brownish pus, gas

bubbles under the skin, skin discoloration, and a foul odor. It is the

rarest form of gangrene, and only 1,000 to 3,000 cases occur in the

United States each year. It can be fatal

if not treated immediately.

Clostridium perfringens,

Gram Stain. Most clostridia are renowned for staining "Gram-variable".